Written by Alexandra Nitoiu

Illustrated by Juliet Ko

At this time of year, some animals are eating and sleeping more than usual to prepare themselves for the frigid weather ahead—and for their long winter ‘nap’. You see, these animals protect themselves in the harsh winter conditions by hibernating. Right now, you’re probably picturing a bear falling into a deep sleep throughout the winter, but there’s actually more to the story!

Let’s start from the beginning: animals hibernate and lower their metabolism because it helps them conserve energy. Metabolism refers to chemical reactions in an organism that convert food into energy to sustain life, so lowering their metabolism means that the organism stores more energy instead of using it. One of the things that metabolism can regulate is body temperature. On one hand, we have ectothermic animals whose body temperature depends on the temperature of their environment; on the other hand, we have endothermic animals which can regulate their own body temperature by generating internal heat (us humans are one of them!). When it gets cold in the winter, endotherms need energy to keep themselves warm but the cold temperatures and lack of food make it challenging. So to conserve energy and survive, many endothermic animals enter a state called ‘torpor’.1

During torpor, physiological processes like breathing, heart rate, and metabolism slow down, causing the body temperature to drop. Animals are usually in a torpor state for less than a day as the technique is only meant to help the animal survive during a short and particularly taxing period—such as a very cold night.1 And as it turns out, hibernation is essentially a series of torpor sessions that each last for many days! Compared to regular torpor, hibernation is more extreme, meaning that it usually involves much lower body temperatures and metabolic rates.1 It also tends to be seasonal, and instead of waking up and finding food normally like animals that go into daily torpor, hibernating animals rely either on their body fat or on stored food.1

In summary, hibernation can be described as a state of minimal activity and slowed metabolism that animals enter in order to survive harsh weather conditions and a low supply of food, usually during winter months. Metabolism can decrease to less than five percent of what it usually is; for example, dwarf lemurs reduce their heart rates from over 300 beats per minute to less than six!2 But the astonishing changes don’t stop there; in some animals, their breathing can stop for more than an hour, their brain activity can become undetectable, and their body temperature can even drop to below freezing!2 These changes are much more dramatic than those associated with normal sleeping, which is why they’re not considered the same. Some scientists even think that hibernators have to periodically pull themselves out of hibernation so that they can actually sleep!2

At this point you might be wondering what sorts of animals hibernate. Mammals, amphibians, reptiles, insects, one bird species (common poorwill), and one fish species (Antarctic cod) undergo hibernation.2 Small animals are more likely to hibernate than larger ones for many reasons. It takes a long time and a lot of energy for larger animals to warm up from hibernation, which isn’t very practical.1 Smaller animals are also more likely to use hibernation to survive harsh conditions which they can’t escape by migrating like larger animals can.1 Lastly, smaller animals have a larger surface-area to volume ratio, meaning that they have a smaller internal volume compared to the surface area of their skin. This causes them to lose heat faster through their skin, making it harder to stay warm in the winter.1,2 As a result, the average hibernator only weighs about as much as an egg!2

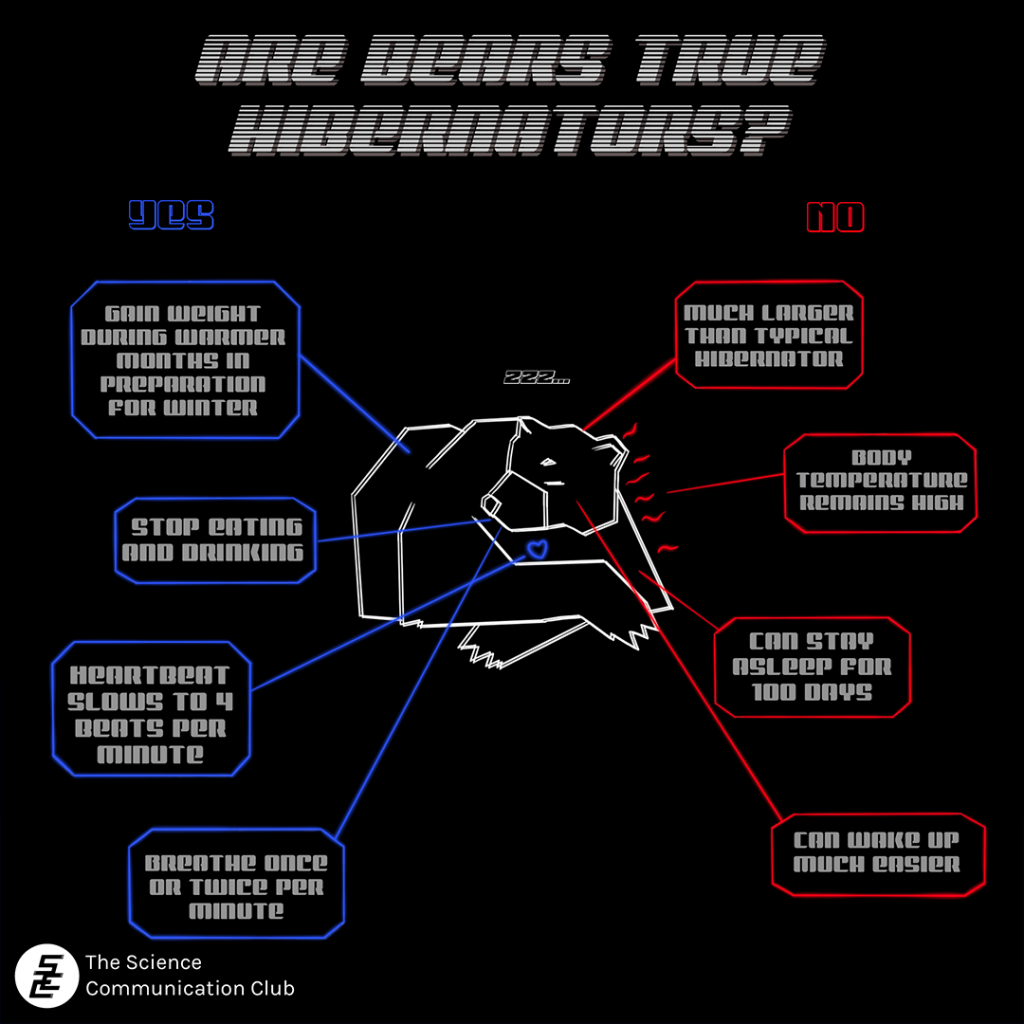

Although we’ve mentioned many hibernating species so far, we haven’t talked about the well-known ones: bears. This is because despite what we commonly believe, scientists aren’t sure whether bears should be considered true hibernators or not. For starters, bears are much larger than the typical hibernator and during hibernation, their body temperature remains relatively high and only drops by a few degrees.1 And unlike other hibernators that wake up periodically, bears can stay in that state for around 100 days!1,2 They can also wake up much easier than typical hibernators,2 and can move around and feed their young even while typical hibernators appear stiff and frozen.1

For all their differences however, they share quite a few traits with other hibernators. They eat a lot and gain weight during warmer months in preparation, gaining up to 13 kilograms per week—that weighs almost as much as an entire wolf!1 And when winter arrives, bears retreat to their dens and stop eating, drinking, and exercising until they wake up months later with much less fat on their frame.1 Their heartrates slow down to 4 beats per minute and they breathe only once or twice per minute.1 These similarities suggest that their winter routine is much like hibernation, even if it’s not the real thing.

But harsh conditions aren’t only restricted to the depths of winter: some animals hibernate when food is scarce, such as echidnas in Australia that hibernate after wildfires.2 Others like earthworms, snails, amphibians, and reptiles (including Nile crocodiles!) escape extreme heat or drought through aestivation, a process that’s like hibernation, only for hot climates.3 Many of them bury themselves in the ground to be protected from the heat and wait for wetter or cooler weather.3

Unfortunately, climate change and rising temperatures have been causing hibernating animals to stay active for longer during periods when they’re awake, making them lose precious energy.2 If too many animals perish during taxing periods because they run out of energy, entire species could be driven to extinction. But hope is not lost quite yet! There’s the Fat Bear Week: an annual tournament which encourages internet users to vote for the bears they think have gotten the fattest to promote conservation efforts.4 You see, many large brown bears live at Brooks River in Katmai National Park, Alaska, and the tournament is “celebrating their success in preparation for winter hibernation.”4 The bears need to stock up on salmon and fatten up in order to survive ‘hibernating’ through the winter. Last year’s winner was bear number 480, named Otis, with more than 96 thousand votes being placed in the final round! This year’s tournament is being held from October 5 to October 11, so get your votes ready! And if you’re looking for something to do after the tournament, you can always raise awareness about smaller hibernators that need protecting!

Sources:

- Grigg, G., Geiser, F., Nicol, S. & Turbill, C. Not just sleep: all about hibernation. Australian Academy of Science (2016). Available at: https://www.science.org.au/curious/hibernation

- Wilcox, C. Animals Don’t Actually Sleep for the Winter and Other Surprises About the Science of Hibernation. National Geographic (2017). Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/animals-hibernation-science-nature-biology-sleep

- Price, J. What is hibernation? BBC Wildlife Available at: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/what-is-hibernation/

- Fat Bear Week 2022. Katmai National Park and Preserve (2022). Available at: https://www.katmaiconservancy.org/fat-bear-week-2022/ (Accessed: 4th September 2022)