Written by Quinn Lui

Illustrated by Christine Lancion

Browse through any website with clickbait ads for long enough, and chances are high you’ll eventually see a headline about a nail polish horror story. Maybe someone bought a cheap bottle of polish which made their nails or fingers start to rot. Or maybe a salon trip ended with third-degree burns. However, this hasn’t stopped hordes of people from showing up to their favourite salons for a manicure, or trying to recreate the latest trends at home. Plus, even though nail polish has been historically marketed towards women, it’s quickly becoming a gender-neutral fashion statement.

Given the popularity of nail-painting, it’s no surprise that we tend to assume those horror stories are nothing more than hoaxes. But, as it turns out, those pretty bottles of polish can have significant effects on human health and the environment—unassuming as they may seem at first glance.

In a deep-dive look into women’s nail health, researchers Jessica Reinecke and Molly Hinshaw observed that many types of nail cosmetics have destructive effects on the nail’s strength or structure and the skin around the nail. This can worsen the hands’ appearance in the long run—even though the short-term goal of painting your nails is often to improve their appearance. For instance, many older nail polish formulas contained an ingredient called tosylamide/formaldehyde resin. This was a common allergen, often causing an itchy and unsightly rash formally known as allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Fortunately, due to the highly visible and widespread nature of this side effect, tosylamide/formaldehyde resin is rarely used in current polishes.

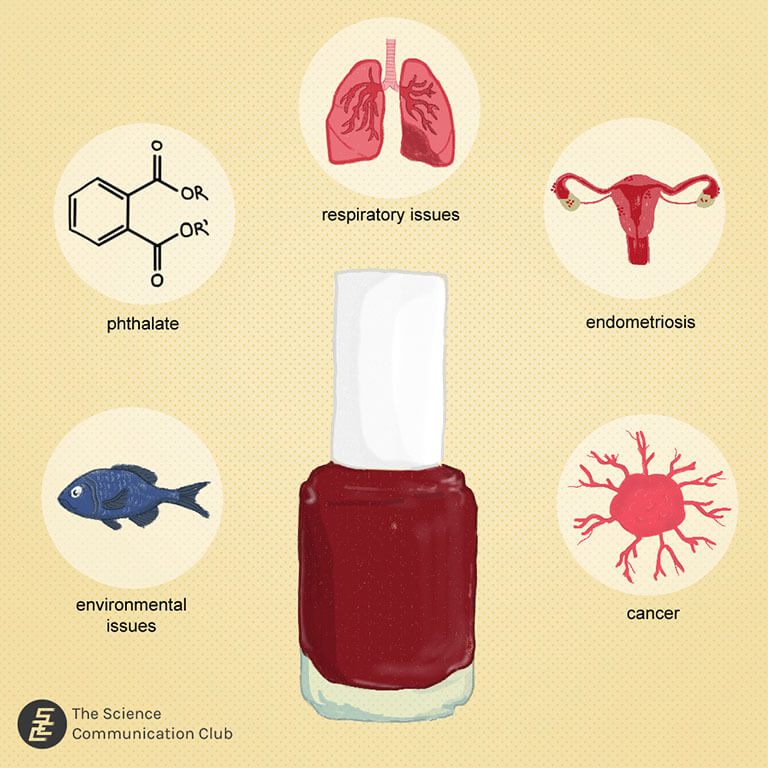

It’s also important to keep in mind that not all the negative effects of nail cosmetics are so immediately noticeable. When that’s the case, nail polish companies are far less motivated to alter them. A recent study done by researchers at the University of Toronto assessed the air in nail salons for levels of harmful chemicals. Most of these were phthalates, which are chemicals added to plastics in order to make them more durable. On a bottle of nail polish, the presence of phthalates translates to the claim that a certain formula is particularly chip-resistant, long-lasting, or able to hold up to extreme wear. In a salon setting, this raises concerns about the high level of exposure that employees are experiencing. For instance, the study reported that the chemical TPhP, which is used in some polishes, was found at levels ten times higher than in commercial recycling facilities.

In the long term, phthalates and other chemicals have been connected to an increased risk for a whole host of potential health issues. These include asthma, various cancers, endometriosis, a variety of reproductive problems, or even nervous system damage—just to name a few. Existing research tends to focus on the possible effects of a single hazardous substance, or a group or similar ones, which doesn’t account for the cocktail of chemicals that nail industry workers are exposed to on a daily basis. These workers have a long-documented history of suffering from skin, eye, and respiratory issues at a high rate, which many believe are tied to their working conditions, even if few research studies have looked into the exact causes of the problem.

To complicate matters further, many salon employees may work while pregnant, or bring their children to their workplace in lieu of seeking alternative childcare. Prenatal exposure to various chemicals found in nail polish has specifically been associated with harmful outcomes in children, including decreased cognitive capabilities, such as problems with working memory.

Outside of the nail salon, polish disposal poses problems, too. Bottles of polish have infamously short lives, quickly separating into layers of pigment, or becoming thick and sticky. Even a nearly used-up bottle will still have plenty of residue clinging to its sides. Nail polish is classified as a hazardous household waste, and should be taken to a specialized depot to be properly disposed of. However, many of us are guilty of simply tossing a bottle into the trash when it’s outlived its use, thinking that such a small thing can’t do much harm—but those effects add up. When fish are exposed to chemicals released by nail polish, they’ve been observed to experience developmental and reproductive issues, in an eerie echo of the health effects in nail industry workers and their children.

In a review of the industrial chemicals found in lipsticks and nail polishes, Shuqin Tang and colleagues noted that some of the ingredients they found at high levels aren’t currently well-known as pollutants in the world of environmental health research. This suggests that their presence in the environment—and, consequently, any potential effects—may rise sharply, the more we use these cosmetics.

Does this mean you should never get your nails done again? Not necessarily. At the moment, responsibility for the health of nail industry workers falls mainly on the shoulders of their employers and the workers themselves. Employers are expected to provide well-ventilated venues and personal protection equipment, as well as purchasing products with less hazardous ingredients when possible. Nail salons that strive to keep their employees safe deserve support! Ultimately, though, the health and environmental threats posed by nail polish can be traced back to the manufacturers. As shown in the case of tosylamide/formaldehyde, alternatives to harmful substances can be found. Similar changes could happen with the ingredients that pose less visible health threats—so long as consumers make their displeasure known.

To find out when and where you can dispose of your used nail polish in Toronto, consult the city’s Household Hazardous Waste page. If you’re located elsewhere, you can also Google “household hazardous waste disposal” plus wherever you live.

Check out the Nail Salon Workers Project to learn more about nail salon issues in Toronto, in the words of the nail industry workers themselves.

Sources:

- Felzenszwalb, I., Fernandes, A. D. S., Brito, L. B., Oliveira, G. A. R., Silva, P. A. S., Arcanjo, M. E., Marques, M. R. D. C., Vicari. T, Leme, D. M., Cestari, M. M., & Ferraz, E. R. A. (2019). Toxicological evaluation of nail polish waste discarded in the environment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 27590–27603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1880-y

- Fung, K. (2014). Gel, acrylic, or shellac: The impact of Southeast and East Asian immigrant nail salon workers on the health care system. University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender, and Class, 14(1). http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc/vol14/iss1/5

- Nguyen, L. V., Diamond, M. L., Kalenge, S., Kirkham, T. L., Holness, D. L., & Arrandale, V. H. (2022). Occupational exposure of Canadian nail salon workers to plasticizers including phthalates and organophosphate esters. Environmental Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04974

- Park, S. A., Gwak, S, & Choi, S. (2014). Assessment of occupational symptoms and chemical exposures for nail salon technicians in Daegu City, Korea. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 47(3), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.2014.47.3.169

- Reinecke, J. K., & Hinshaw, M. A. (2020). Nail health in women. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 6(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.006

- Tang, S., Chen, Y., Song, G., Liu, X., Shi, Y., Xie, Q., & Chen, D. (2021). A cocktail of industrial chemicals in lipstick and nail polish: Profiles and health implications. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 8(9), 760–765. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00512