Written by Dorothy Zeng

Illustrated by Jasmine Fu

For a large percentage of the population, sports are more than just a pastime or a hobby. We all know the one uncle who watches a game in the living room, yelling or cursing or cheering every couple of minutes. Occasionally, you might hear a cry of despair echo from the living room. If curiosity tempts you, you might enter the living room to see your uncle cursing in frustration as his favourite player on his favourite team collapses in the middle of the field, clutching their knee. The game stops abruptly, and medics rush onto the field. Before you can even figure out what’s going on, the commentators start musing about how this might be a “career-ending ACL injury” and wondering how the team can cope with the loss. While this type of injury may be a foreign concept to non–sports fans like you or me, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries or tears are one of the most common knee injuries in athletes.¹ The reason why your uncle is so distraught is because only about 65% of athletes with ACL injury return to their previous level of sport while a smaller 55% return to competitive sports at all.² In a sense, this injury could be the end of a player’s time in the field.

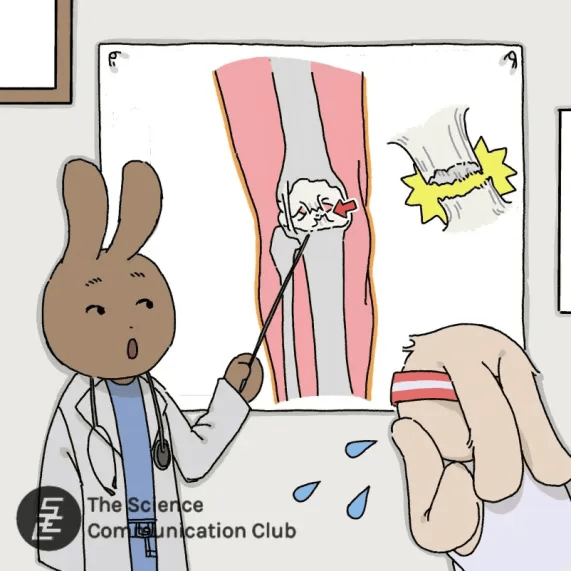

You might be wondering: is the ACL really that important? If it’s that common of an injury, why isn’t it guaranteed that athletes go back to playing sports after their treatment? The ACL is one of the major ligaments in the knee responsible for stabilizing it. When we are in motion, the ACL prevents the leg from moving in front of the thigh or twisting in a way that it’s not supposed to.³ When the ACL gets injured, the knee becomes a lot less stable and more prone to collapsing into itself. The most common treatment for ACL injuries is an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR), where a tendon or ligament from somewhere else in the body is used to replace the ACL. Because it allows for greater joint stability,⁴ most athletes choose this option as it provides a greater chance for them to return to their previous level of fitness. Unfortunately, ACLRs are not always successful. Around one third of patients will reinjure the ACL up to 5 years after ACLR,⁵ and the risk of injuring the opposite leg after returning to sport is also higher.⁶ A reason for this high reinjury rate is strength deficits in both legs following an ACL injury.⁷ Our muscles shrink, or atrophy, due to lack of exercise, and this certainly happens if we are forced to sit all day. Athletes are forced to remain sedentary after an ACL injury. A study found that muscle volume decreased by 7.8% along with a 47% decrease in muscle power following 20 days of bed rest.⁸ This means that athletes usually come out of surgery with both legs weaker than before they were injured.

Limb symmetry is a common test used to assess knee function and readiness for return-to-sport (RTS).⁶ The test basically determines the injured limb’s progress back to preinjury capabilities by using the opposite limb as a benchmark. Unfortunately, even after patients pass the test, there still seems to be a significant difference in leg strength between healthy participants and individuals who have undergone an ACLR.⁹ With the loss of strength in both legs, using limb symmetry can overestimate an athlete’s readiness to RTS and overlook significant strength deficits in both the injured and uninjured limb. As mentioned before, this can increase the rate of reinjury and stop athletes from returning to their sport.

The field of ACL research is constantly evolving with new techniques and rehabilitation strategies developed to improve an athlete’s recovery. Unfortunately, as of right now, it seems like there is still some time before we can ensure that your uncle’s favourite player can return to the field.

Sources:

- Kaeding CC, M.D., Léger-St-Jean B, MD, Magnussen, Robert A.,M.P.H., M.D. Epidemiology and diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Clin Sports Med 2017;36(1):1–8.

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med 2014;48(21):1543–52.

- Siegel L, Vandenakker-Albanese C, Siegel D. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries: Anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, and management.

- Smith TO, Postle K, Penny F, Mcnamara I, Mann CJV. Is reconstruction the best management strategy for anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction versus non-operative treatment. The Knee 2014 -03;21(2):462.

- Webster KE, Feller JA. Exploring the high reinjury rate in younger patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2016;44(11):2827–32.

- Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Where are we in 2022? Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation 2022;4(1):e77–82.

- Filbay SR, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Practice & Research.Clinical Rheumatology 2019;33(1):33–47.

- Kubo K, Akima H, Kouzaki M, Ito M, Kawakami Y, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. Changes in the elastic properties of tendon structures following 20 days bed-rest in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 2000;83(6):463–8.

- Gill VS, Tummala SV, Han W, Boddu SP, Verhey JT, Marks L, Chhabra A. Athletes continue to show functional performance deficits at return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2024;40(8):2309,2321.e2.