Written by Aaliyah Mulla

Illustrated by Angela Lin

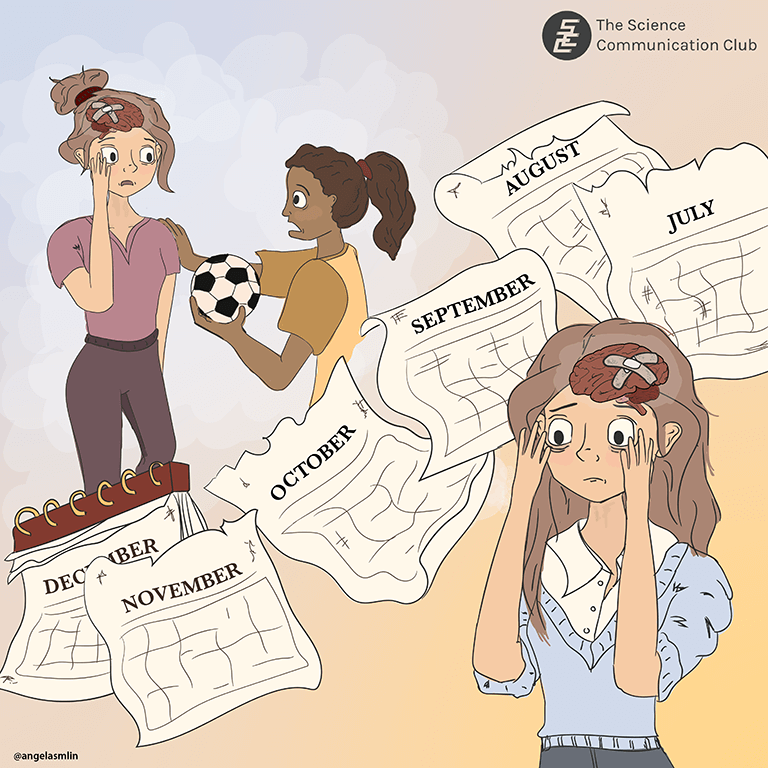

You’re walking in the park with some friends, in the middle of a lively conversation, when suddenly your head is thrown back by something smacking into it. Ouch. The world spins a bit, and your head hurts. Your stomach churns with nausea. The kids on a nearby field are looking at you shocked, apologizing as they retrieve their soccer ball from the ground near you.

On the insistence of your friends, you go to the emergency room. The lights are too bright, and the waiting room echoes with the sounds of people speaking, an incessant hum underneath it all. Was the world always this loud? Hours go by, your symptoms getting worse by the minute. Finally, it’s your turn to be seen. At this point, you’re too exhausted to describe your symptoms to the doctor, but you try your best, and with the help of your friends, you manage to convey what happened. The doctors run some tests and tell you to rest it out. You should be good to go in a week or two. Two weeks turn into three, which turn into a month, and before you know it, two months have gone by with no improvement in your symptoms. You’re referred to a neurologist, who tells you some people just take longer to heal. You’ll just have to wait it out.

This is the reality faced by many people following a head injury. While most people recover from concussions within a couple of weeks, about half of concussion patients report symptoms for multiple months, with 10-15% of them reporting symptoms for more than a year after a head injury. When concussion symptoms last for longer than expected, it’s called post-concussion syndrome (PCS). One of the biggest problems is that a lot of people don’t fully understand post-concussion syndrome, including many healthcare professionals. Though people with PCS technically don’t have a concussion at present, people dealing with PCS still experience many of the same concussion symptoms at an equal or higher level than people with typical concussions. They simply take longer to heal. Unlike a broken leg, the symptoms of a concussion may be hard for others to see, making it tricky for people to understand. This can make it hard for concussion patients to get the accommodations they need to support their recovery, and cause challenges for them as they navigate social relationships and consider returning to work. When the symptoms last for a long time, as is the case in PCS, these effects have an even bigger impact on a person’s life.

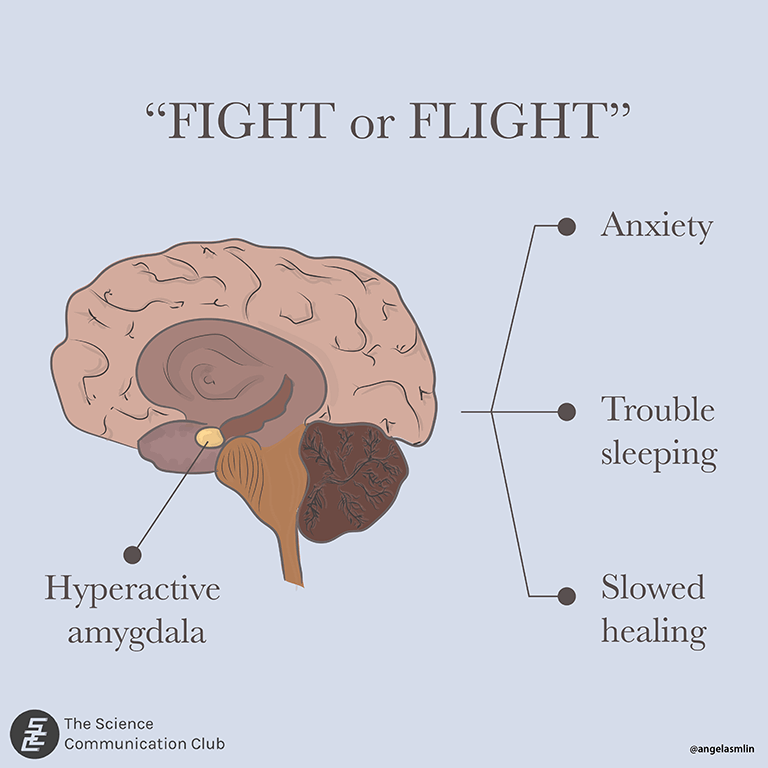

Concussions are systemic in nature, which means they can affect multiple areas of the body. This makes sense, given that concussions are a form of mild traumatic brain injury, and our brains are at the centre of just about every bodily function. Imagine if the control centre of your body went into emergency mode. Your body is so busy trying to heal that there are no resources left for normal daily functioning. To make matters worse, your brain might be so stressed that it’s stuck in fight or flight mode. Think about that time when you were walking home alone in the dark, on high alert because you weren’t sure of your safety. Or that time you were scrambling to get an assignment submitted five minutes before the deadline. Your heart was probably beating fast, palms a little sweaty, body tense. You might not have been the most focused, and if anyone tried to talk to you, you were probably too on edge to respond normally. Now imagine if you felt similarly to that for weeks on end. During PCS, many people’s brains are stuck in a version of fight or flight mode. In this mode, a part of the brain called the amygdala is kicked into gear and operating with much more activity than usual. It coordinates the body’s stress response, which can be responsible for many PCS symptoms. For instance, many people experience anxiety during PCS and have trouble sleeping. Normally, these effects would be useful—there’s no time to sleep if you’re being attacked by a bear! However, when there’s no actual emergency to deal with, having this response consistently active can be exhausting and can actually prevent our brains from healing properly. If the body thinks it’s in danger, it won’t use precious resources trying to heal. With this in mind, strategies to treat anxiety may be beneficial for some PCS patients, such as mindfulness meditation or psychotherapy.

The good news is that with time, proper treatment, and (a lot of) patience, people can make full recoveries from PCS. Everyone experiences PCS differently, so it might take a while to figure out what treatment strategies work for an individual. However, once a medical professional can find the underlying causes of the symptoms, there are strategies that can be used to promote brain healing. One of the most important things you can do to promote healing is to maintain a healthy lifestyle. This means eating healthy, engaging in light exercise, and trying to get enough sleep. A large part of healing is also knowing when to push yourself, and when to take breaks. Many people experience sensory overload during PCS, so turning off excess lights and reducing noise in your environment can be very helpful for managing concussion symptoms. Certain tasks tend to make people’s symptoms worse. For instance, many people have trouble concentrating, planning, or multi-tasking. Understanding these triggers can help people with PCS prioritise their tasks and manage their time. If you know cooking will trigger your symptoms, you may need to plan a break before and after cooking to avoid overloading your system. If you know someone with PCS, don’t be offended if they ask you to stop talking to them while they complete a task. Multi-tasking can be extremely challenging, so you may just need to save the conversation for later. Like other long-term conditions, people with PCS will have good moments and bad moments. Just because they can do something with ease one day, doesn’t mean they’ll be able to do the same the next day. Likewise, they may seem perfectly fine at one moment and then utterly exhausted when you see them again an hour later. It’s important to understand that these fluctuations are natural and part of the healing process. Of course, all of this is just general advice (largely from personal experience), and is not meant to be medical advice. If you’re experiencing PCS, be sure to consult a medical professional (or maybe a few) for medical advice.

Below are a few resources that were helpful for a loved one while they recovered from PCS, and which provide more in-depth information about the condition. It may seem like there are limited professionals around with in-depth knowledge of concussions, but there are many professionals specializing in concussion if you know where to look.

Resources

- https://completeconcussions.com/resources/educational-resources/

- https://completeconcussions.com/drive/uploads/2021/04/CCMI-Concussion-Handbook-2021-min.pdf

- https://concussiondoc.io/offer/the-concussion-fix/

- https://hollandbloorview.ca/persistent-symptoms-services

Sources:

- Complete Concussion Management. (2021, April 28). About concussion: Complete concussion management. Complete Concussion Management Inc. Retrieved April 2, 2022, from https://completeconcussions.com/resources/educational-resources/

- Pedersen, T. (2021, October 14). Amygdala hijack: What it is and how to prevent it. Psych Central. Retrieved April 2, 2022, from https://psychcentral.com/health/amygdala-hijack#symptoms

- Spinos, P., Sakellaropoulos, G., Georgiopoulos, M., Stavridi, K., Apostolopoulou, K., Ellul, J., & Constantoyannis, C. (2010). Postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in Western Greece. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection & Critical Care, 69(4), 789–794. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0b013e3181edea67

- Zhang, X., Ge, T. tong, Yin, G., Cui, R., Zhao, G., & Yang, W. (2018). Stress-induced functional alterations in amygdala: Implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00367

Special thanks to Safeera Mulla for using her lived experience to provide insight into life with PCS.