Written by Sabrina Zaidi

Illustrated by Maggie Huang

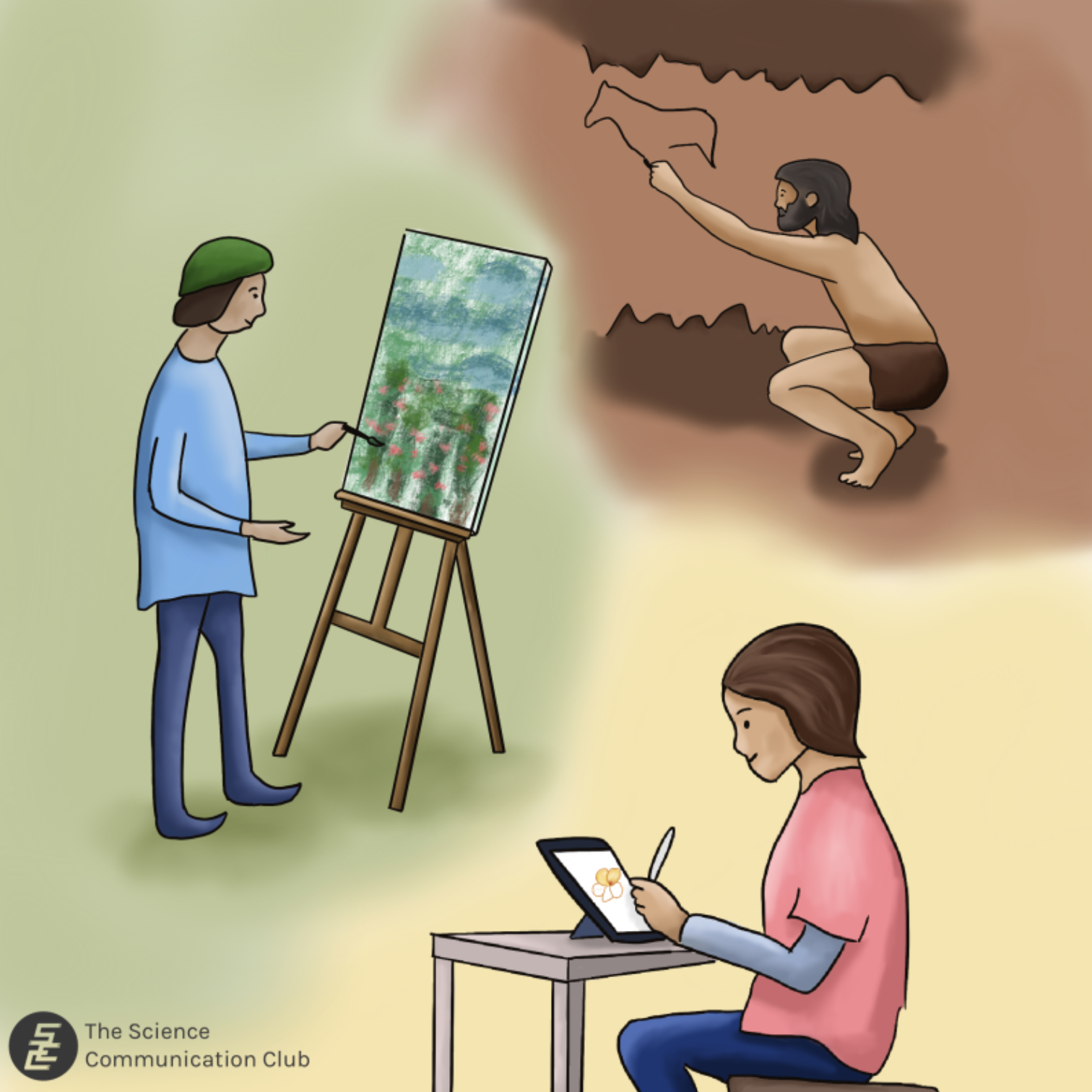

What sets humans apart from other animals? Among our standout intelligence, opposable thumbs, and use of language, artistic creativity is another trait that separates us from other species. While the other traits can have clear benefits to our survival, philosophers, scientists, historians, and anthropologists have all pondered the same question: what has art done for us? For artistic creativity to not only remain within our species, but also continue to advance alongside our development, it would have needed to be useful for the survival of our species. Under the evolutionary theory of “survival of the fittest”, the genetic traits best suited for the environment at the time are typically the ones that get passed onto the next generation through the enhancement of an individual’s survival or ability to have children.¹ It makes sense why certain traits were successful for our early human ancestors – like high endurance to help us hunt or coloured vision to help us find ripe fruits.²,³ But what about the visual arts? From a direct sense, art doesn’t help us hunt, acquire food, or produce offspring, yet we’ve done it since the dawn of our ancestors.

The earliest form of art is thought to have been from around 164,000 years ago, when our early Homo sapien ancestors painted their skin with ochre as body art in South Africa.⁴ Other forms of body decorations like pigments or beads have also been found in South African caves around 100,000 years ago.⁴ This stage of body decoration likely stemmed into other forms of visual art like cave drawings and carvings.⁴ As mentioned, it has long been a mystery as to why we evolved such an appreciation and knack for creating visually aesthetic pieces to begin with.⁴ To bring this puzzle together, we’ll take the story back to when humans were developing communication. Body art like body painting, and thereafter, the development of necklaces, was thought to indicate the status of the wearer or maker of the piece.⁴ Aside from symbolic reasons, face-painting may have also been useful for camouflage when stalking prey, suggesting that potential ritualistic or symbolic uses of art may have originated as a skill to improve survival through camouflage.⁴

The first known piece of art that was created separate from the body included a decorative zig-zag pattern found on a piece of ochre around 77,000 years ago in South Africa.⁴ Other early pattern designs have been found as simple parallel lines, curves, and more zig-zag patterns on bones within Europe, which may have been connected to both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens.⁴ Such patterns are thought to have originated from the visual experience of entoptic phenomena – visual effects sourced from within the human eye or brain.⁴ Beyond simple patterns, our early Homo sapien ancestors continued to evolve lines into more meaningful symbolic shapes through mediums such as petroglyphs or rock engravings.⁴ 30,000 years ago, we began to create art of flat surfaces, like drawings of animals or handprints on rock walls and other flat surfaces.⁴ Since then, art has evolved even further as we broadened our range of materials, developing 3-dimensional figurines, architecture, sculptures, paintings, and more, resulting in the plethora of artistic genres and mediums we have in the present-day.

There are multiple indicators and hypotheses pointing to the reason for artistic creativity, all of which converge at the fact that humans are uniquely capable of higher artistic processing due to our relatively large brain size compared to other animals.⁴ However, this observation only goes as far as to suggest the reason, but not the complexity of artistic creativity.⁴ The modern human has the same anatomical brain size as a Neanderthal, despite having very different levels of complexity in artistic skills.⁴ Even the variation in artistic creativity among humans is so different that we cannot explain it solely from an anatomical lens.⁴ As a result, we look for clues in archaeological remains like tools.⁴ One hypothesis suggests that the prehistoric development of tools may have a connection to the development of artistic culture in Homo sapiens due to the transferrable skills needed to create and refine tools based on visualization, similar to the way we create art.⁴ Art may have then proliferated as a method of storytelling, providing the ability to easily communicate mythology, spirituality, and concepts of the body and death through symbolic imagery.⁴ From a directly practical standpoint, art may have also played a role in hunting. During a chase, most other animals surrender the hunt once their prey escapes the range of their senses.⁵ Early humans however, knew that their prey may still exist hidden behind a rock, or past the horizon they could not see anymore.⁵ Given our endurance-based hunting style, it was crucial to be able to apply artistic skills like imagination, logic, and visualization to be able to comprehend the continued existence of prey once it evaded our sight.⁴ As a result, artistic skill and the enhancement of this ability would have provided us with a significant evolutionary advantage for the survival of our species.⁴

As society developed, so did art. In order to be seen and recognized, art must be viewed through the human context where themes of hunting, fertility, and social cohesion were fundamental for the advancement of humanity.⁴ This contribution to human development may be one of the many reasons we continue to possess artistic creativity. To this day, we continue to push the boundaries of creative expression which brings us closer to each other. Among its many uses, appreciation for the visual arts has become intertwined with our hobbies, interests, culture, and topics of conversation in the modern day. As we continue to understand how art intertwines with our evolutionary history, we can be sure that it is one of the key defining features of what makes us human.

Sources:

- Cunningham C. Survival of the fittest. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2024 Mar 14 [accessed 2024 Apr 17]. https://www.britannica.com/science/survival-of-the-fittest

- Hunter P. The evolution of human endurance. EMBO reports. 2019;20(11). doi:10.15252/embr.201949396

- Bompas A, Kendall G, Sumner P. Spotting fruit versus picking fruit as the selective advantage of human colour vision. i-Perception. 2013;4(2):84–94. doi:10.1068/i0564

- Morriss‐Kay GM. The evolution of human artistic creativity. Journal of Anatomy. 2010;216(2):158–176. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01160.x

- Heinrich B. Racing the antelope: What animals can teach us about running and life. New York: Harper Collins; 2001.