Written by Mashiyat Ahmed

Illustrated by Christina Sheppard-Greenhow

In recent decades, the surge in extreme climate events—floods, hurricanes, heat waves, and droughts—have devastated communities and brought into question the catastrophic violence of nature. Our technological feats as a society are reaching new heights, allowing governments, industries, and companies to use—if not exploit—nature to serve human interests. Yet, no matter how much control we have as humans, it seems that nature always has the final say.

Our planet, though young compared to other celestial bodies that speckle the universe, is very old. Geologists use the “geological time scale”—a chronological timeline that categorizes Earth’s 4.5-billion-year-old existence based on distinct geological or paleontological events—to understand how evolution has changed the circumstances of life on Earth. Fossil records, changes in geology and climate, and what type of species roam the Earth are all characteristics that distinguish one stretch of time from another.

Extinctions are examples of unfathomably catastrophic events that have littered Earth’s history.

Extinctions happen when a considerable percentage of species disappear during a relatively short period of time. Mass extinctions, however, are when more than 75% of all Earth’s species disappear during a geologically short period of time. During mass extinctions, massive tsunamis, thundering skies, unpredictable weather patterns, and volcanic outbursts shake ecosystems’ harmony out of balance, damaging habitats, disrupting food chains, and preventing the sun’s life-giving energy from reaching Earth.

However, in the ebb and flow of evolutionary progress, extinctions are normal, occurring naturally and periodically over millions of years to shape present-day ecosystems. Evolution is the scientific mechanism that shapes a species and its environment according to characteristics most beneficial to life’s survival. As species interact with their rich environments, physical features and behaviours that facilitate the survival of the species become genetically coded and passed down to subsequent generations. Over time, certain features and even entire species get wiped out if they accumulate enough traits that aren’t conducive to their survival. According to evolutionary logic, extinction events are not only normal, but necessary for maintaining a wider balance of flora and fauna: geologically, evolution happens through a balance of extinction and speciation—the creation of new species due to new evolutionary and adaptive pressures. When certain species go extinct, opportunities for new species and ways of life emerge out of the chaos of extinction.

This is a testament to how nature both ruins and creates.

Throughout its 4.5-billion-year history, our planet has gone through five major extinctions—the most popular of which killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago—that have shaped the biodiversity, natural environments, and the evolutionary pressures. But how do catastrophic events that are designed to obliterate life on Earth end up creating new life?

Species are fundamentally supported and designed by their environments.

Extreme environmental changes triggered by cataclysmic events—such as rapid changes in climate or volcanic debris replacing saturating the atmosphere—are able to wipe out entire evolutionary lineages: the species that aren’t equipped to survive in the new post-extinction climate are destined to die out.

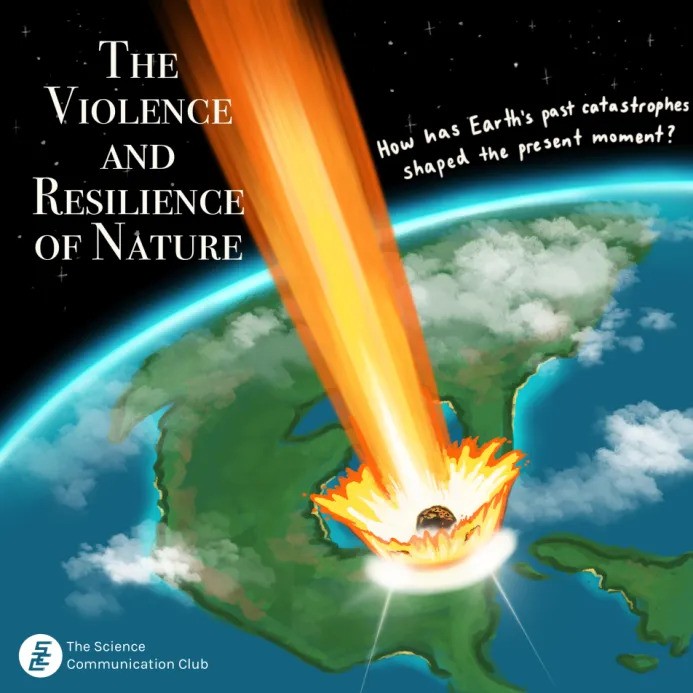

The most recent mass extinction occurred 65 million years ago, during the end-Cretaceous period. An asteroid, known as the Chicxulub impactor, struck the Yucatan Peninsula in present-day Mexico with a whopping velocity of 20 kilometers per second, causing widespread devastation.

Originating from the emptiness that lies at the end of our solar system, this asteroid was relatively small—the size of Manhattan, NY—yet its unimaginable speed upon impact instantly gave rise to tsunamis and volcanic eruptions, blanketing the Earth in a dome of burning debris and releasing energy equivalent to 100 million nuclear bombs.

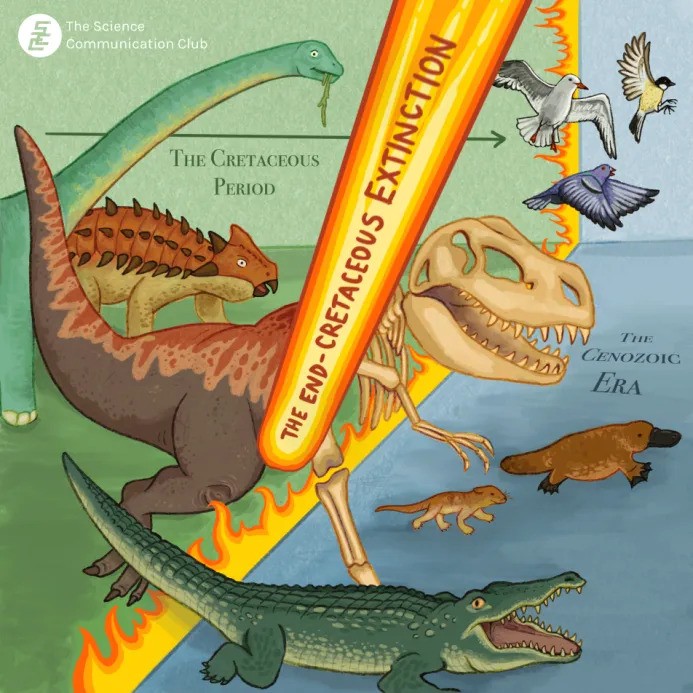

All species within a few minutes of impact vaporized into nothingness. Plants were no longer able to photosynthesize energy from the sun to support the food chain, essentially creating mass starvation for herbivores and carnivores. The only species that survived this violence were dinosaur-like bird species and smaller mammals that weighed less than 25 kg. A combination of diverse diets, aviation, and size ensured that birds could better adapt to environmental conditions left behind by the asteroid.

The birds we see roam our skies today descended from the only survivors—the aviation specialists—of the end-Cretaceous extinction. But despite wiping out the majority of Earth’s biodiversity in a geological instant, the death of life, paradoxically, also gave rise to life. Extinction events pose great threat to species, and species that do survive must find creative ways to adapt to their new environments. Despite their deadliness, these extinction events can play a creative role in evolution, churning out new species over vast expanses of geologic time.

During the recovery period of the end-Cretaceous extinction (roughly ten million years), many ecological niches—a role a species plays in its environments specific to the species needs and abilities—were left vacant by species that did not manage to survive, creating opportunities for leftover species to adapt to said niches. For example, for most of prehistoric time, mammals remained as rodent-like creatures. The rapid extinction of dinosaurs prompted the diversification of mammals as they evolved into vacant ecological niches left over by vaporized species.

Right now, the ecological systems that sustain all life on Earth and the species that call this planet home are a result of the surprising creativity of evolution during and after extinctions. Understanding Earth’s geological and paleontological history and how it has shaped the current moment truly makes me appreciate the planet I call home.

Sources:

- Ritchie H. There have been five mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/mass-extinctions

- Nature Education. Evolution. Scitable. 2014. https://www.nature.com/scitable/definition/evolution-78/

- Billings L. We Know the Origins of the Asteroid That Killed the Dinosaurs. Scientific American. 2024 Aug 15. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/asteroid-that-killed-the-dinosaurs-came-from-beyond-jupiter/

- Thanukos A. The role of mass extinction in evolution. UC Museum of Paleontology Understanding Evolution. https://evolution.berkeley.edu/mass-extinction/the-role-of-mass-extinction-in-evolution/