Written by Iyeh Mohammadi

Illustrated by Jenny Zhang

Hidden within the jungles of Cambodia, just a few kilometres away from bustling city of Siem Reap, you can find the remains of majestic sandstone temples and walled fortresses. These are all that’s left of the magnificent city of Angkor, the lost capital of the Khmer Empire. The empire was discovered by the French explorer Henri Mouhot in 1860, and his writings and drawings of the grand temples and pavilions like Angkor Wat thrust Cambodia into the spotlight and led to the restoration of the site as a monument to the lost empire.

Sounds like something straight out of an Indiana Jones movie, right? Well, that explanation contains about just as much truth as those movies do, i.e., not a whole lot. Angkor was the capital of the Khmer Empire for centuries and while Mouhot’s drawings drew wider European attention to it, he didn’t discover Angkor because Angkor was never ‘lost’. Its temples were still visited regularly by Khmer royals and pilgrims from all over Southeast and East Asia. Even as late as the 19th century, monks lived in Angkor Wat until they were forced to relocate by French colonial forces.

The massive stone structures aren’t all that’s left of Angkor either. Archeologists used to think that Angkor Thom, a walled enclave north of Angkor Wat, was where most of Angkor’s residents lived, and it isn’t hard to see why. Spanning 9 square kilometres and surrounded by a moat, Angkor Thom was the heart of the Khmer capital and was thought to be the entire city. However, inscriptions on temple walls indicated that close to a million people lived in Angkor, and as grand as Angkor Thom was, it was too small to accommodate that amount of people. But people tend to exaggerate, especially when they’re talking about their own accomplishments. Could that be the case here?

That’s what archeologists thought, until a team led by University of Sidney’s Dr. Damian Evans mapped thousands of square kilometres around Angkor using LiDAR, revealing the remains of a massive urban landscape beneath the jungle. LiDAR (or simply lidar) stands for ‘light detection and ranging’, and like radar, it works by emitting lasers from a sensor towards a specific point and recording the time it takes for the laser to be reflected back. Basically, it’s like radar but using pulses of light instead of radio waves. However, unlike radio waves, light has a much shorter wavelength which allows for much greater precision.

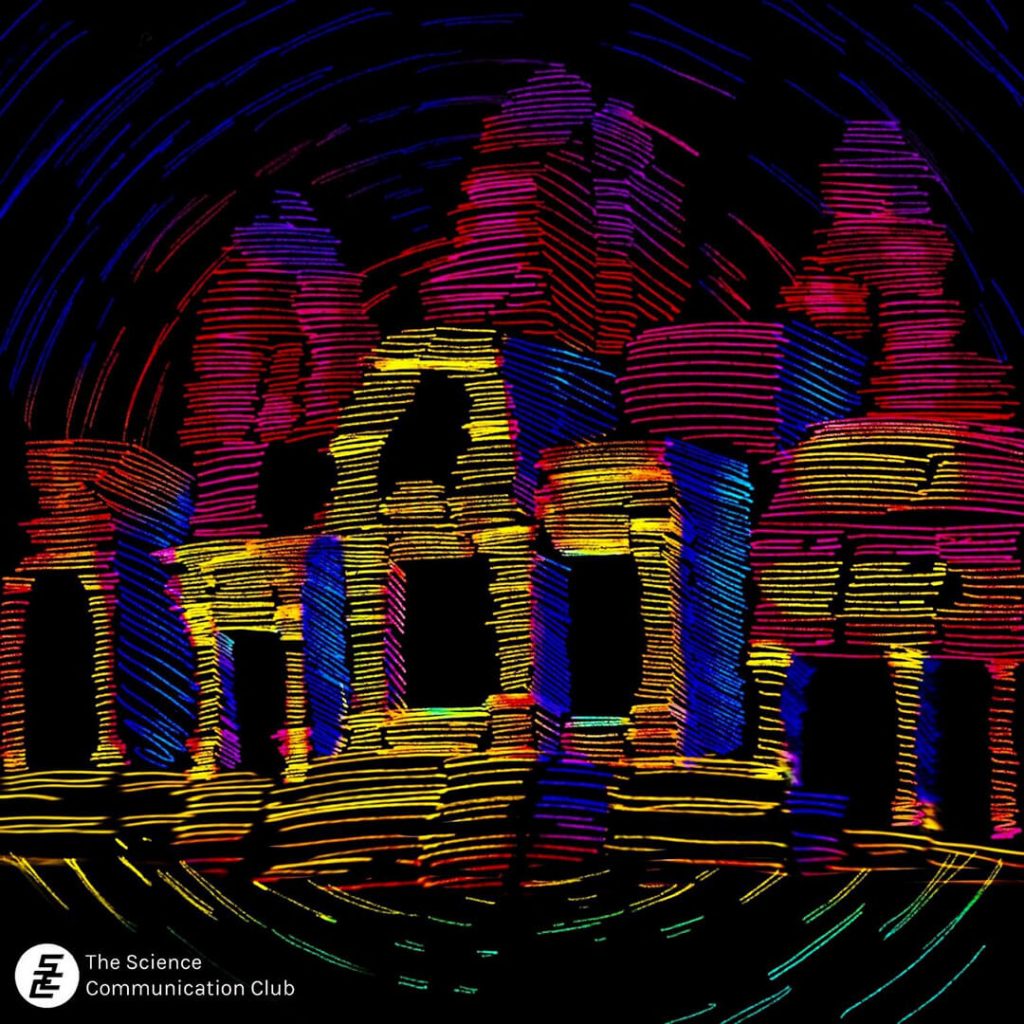

LiDAR sensors used in archaeology are usually mounted on airborne machines like a drones or helicopters and emit up to 600,000 pulses of light per second down towards the earth. These pulses are scattered and bounced off leaves and vegetation before reaching the ground and getting reflected back.The data leads to a ‘cloud’ of points that can be filtered using a software so that only the last shot—which is typically the earth—remains. This can be used to create detailed 3D maps of a location—an incredibly useful tool in areas where it’s hard to traditionally map and excavate like a dense jungle in Cambodia.

After hearing about the successful use of LiDAR at sites in Central and South America, Dr. Evans decided to try it at Angkor. The Khmer Archaeological Lidar Consortium (KALC) was established, and it took two weeks to survey over 300 square kilometres, but the results were stunning. It was previously thought that urban living was restricted mainly to walled cities and temple complexes like Angkor Thom and Angkor Wat. However, LiDAR revealed large grid-like mounds and indentations on the ground within these complexes and surrounding the temples, unseen beneath the canopy of the trees.These were clear signs of human occupation transforming the environment, the remains of massive urban settlements with a sophisticated water system made from organic materials that were lost to time and decay.

Finding these grid-like mounds wasn’t the only surprising discovery: these settlements were ubiquitous and found throughout the area. This indicated that rather than many different towns and villages surrounding the temples, the entire region was one huge (albeit low-density) urban environment surrounding higher density areas around the temple complexes. Imagine a huge valley cradled between mountains and a giant seasonal lake, filled with small fields and thatched houses as far as the eye can see and veined with canals and artificial lakes. Peppered throughout this region are crowded ‘city centres’ with temples that occasionally interrupt the landscape. This is what Angkor would’ve looked like, quite unlike its contemporaries. At its peak, it could house close to a million people and it was one of the biggest cities in the world.

Buoyed by this success, the Cambodian Archaeological Lidar Initiative (CALI) was established as a successor to KALC and further surveys were conducted and continue to this day. Overall, they’ve expanded the mapped range by thousands of square kilometres and uncovered more cities thought to have been buried by time. LiDAR has more than proven its worth as a valuable archaeological tool and as more new sites are discovered and studied, we gain greater insight gain into the ancient world of our ancestors, improving our ability to correct deep-seated misconceptions about the past.

Sources:

- Cambodian Archaeological Lidar Initiative. (2015, April 3). History. CALI. https://angkorlidar.org/history/

- Carter, A. (2013, September 23). The people who lived in Angkor Wat. Alison in Cambodia. https://alisonincambodia.wordpress.com/2013/09/24/the-people-who-lived-in-angkor-wat/

- Carter, A. (2014, October 5). Stop saying the French discovered Angkor. Alison in Cambodia. https://alisonincambodia.wordpress.com/2014/10/05/stop-saying-the-french-discovered-angkor/

- Carter, A. (2021, September 23). Angkor was never a “lost city.” Alison in Cambodia. https://alisonincambodia.wordpress.com/2021/09/23/angkor-was-never-a-lost-city/

- Cascone, S. (2021, May 11). The Ancient City of Angkor Wat Had a Population Larger Than Modern-Day Boston, According to New Archaeological Research. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/angkor-wat-ancient-population-1966958

- Dunston, L. (2020, February 3). Revealed: Cambodia’s vast medieval cities hidden beneath the jungle. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/11/lost-city-medieval-discovered-hidden-beneath-cambodian-jungle

- Evans, D. (2016). Airborne laser scanning as a method for exploring long-term socio-ecological dynamics in Cambodia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 74, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.05.009

- Evans, D. H., Fletcher, R. J., Pottier, C., Chevance, J. B., Soutif, D., Tan, B. S., Im, S., Ea, D., Tin, T., Kim, S., Cromarty, C., de Greef, S., Hanus, K., Baty, P., Kuszinger, R., Shimoda, I., & Boornazian, G. (2013). Uncovering archaeological landscapes at Angkor using lidar. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(31), 12595–12600. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1306539110

- Gugliotta, G. (2018, February 14). Into the light: how lidar is replacing radar as the archaeologist’s map tool of choice. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jun/20/lidar-radar-archaeology-central-america

- Lawrie, B. B. (2014, September 23). Beyond Angkor: How lasers revealed a lost city. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29245289

- Newitz, A. (2022). Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Penny, D., Hall, T., Evans, D., & Polkinghorne, M. (2019). Geoarchaeological evidence from Angkor, Cambodia, reveals a gradual decline rather than a catastrophic 15th-century collapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(11), 4871–4876. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821460116

- Reporter, G. S. (2018, February 14). Laser technology reveals lost city around Angkor Wat. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/18/lasers-lost-city-angkor-wat-cambodia

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021, December 17). Angkor Thom. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angkor_Thom

- Wikipedia contributors. (2022, February 9). Angkor Wat. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angkor_Wat

- Zaylor, A. (2021, July 27). LiDAR Technology in the Archaeology Industry. FlyGuys. https://flyguys.com/lidar-technology-helps-archaeology-industry/