Written by Koko Johnson

Illustrated by Sania Bahman

“You are the dancing queen”

“Oh, I wanna dance with somebody”

“Shut up and dance with me”

These are just a few popular examples of the countless song lyrics that communicate the exuberant feelings associated with dancing. Whether it is a feeling of satisfaction after learning complex choreography, intimacy felt between people embracing during a partner dance, or simply unabashed confidence when grooving behind closed doors, there is something deeply humanizing about dancing.

The use of creative movement to express oneself or represent a group’s identity, dance has both historical and cultural significance. Dating back farther than Ancient Egypt, dancing has remained a staple of many traditions and celebrations across cultures, ranging from weddings and funerals, to school and work functions, or even religious and spiritual rituals.1 Yet, the evolutionary emergence of dance remains a mystery to the many theorists who seek a basis for our dancing capabilities.

Who Can Dance? Who Can Jive?

Depending on how we define dancing, there is great debate as to whether this behaviour is limited to humans.1,2 Scientists have characterized dancing as musical or rhythmic body movements, a competency we share with only several species of birds and a few Asian elephants.1 So, contrary to the many YouTube videos showcasing cats and dogs who know how to boogie, scientists would argue our pets and primate ancestors cannot dance.1,2 Even so, spontaneous and effortless dancing to music is a skill only we exhibit.2 Whether we think we can cut a rug or not, scientists theorize it is our proficiency in imitation that has unlocked the key to our dancing capabilities, and that this imitative mastery has evolved through social learning.1 Additionally, neuroimaging has revealed that tapping our fingers and feet to music and rhythms activates the same regions of the brain involved in imitation tasks with our hands, corroborating the notion that our ability to dance is ultimately a byproduct of our ability to imitate others.1,2

Why Do We All Shuffle Uniquely?

Although, evolutionarily speaking, the latter suggests that all humans are capable of dancing, researchers also suggest upbringing may impact our individual dance skills. For instance, Oxford psychologist Bronwyn Tarr reflects that a mother’s heartbeat, being one of the first rhythms a fetus experiences, may create a rush of hormones and endorphins that set the stage for bonding with others through synchronized movement later in life.3 Moreover, psychologists from the UK argue that being sung to or rocked may allow babies to form neural associations between sound, rhythm, and motion.1 From the University of Toronto Scarborough, Dr. Laura Cirelli and her colleagues assert that infants predict beats before they start walking and display more rhythmic movements to music than in response to speech.3,4 Not long after, we begin mirroring the precise movements of the many people we encounter at home, at school, in sports, etc. In all, it appears that even the childhood stage when we precociously repeat “why are you copying me?” to everyone else’s irritation, forms an essential part of our dancing development.

As we grow older, especially in the years preceding puberty, our heightened awareness of other’s judgement and increasing sensitivity to criticism, may lead to lowered self-esteem and an unwillingness to perform in the spotlight.5 This begins a familiar phase of awkward swaying with hands in pockets, leaned against the gym wall at the school dance. Into adulthood, as we forge our sense of self, we may overcome these insecurities and opt to revel in the positive emotions experienced when dancing in groups.1 Having said that, we may also continue to struggle tearing up the dance floor as adults, but fear not — scientists have some good reasons why it may not be our fault.

What Could Prevent Us From Doing the Hokey Pokey and Turning Ourselves Around?

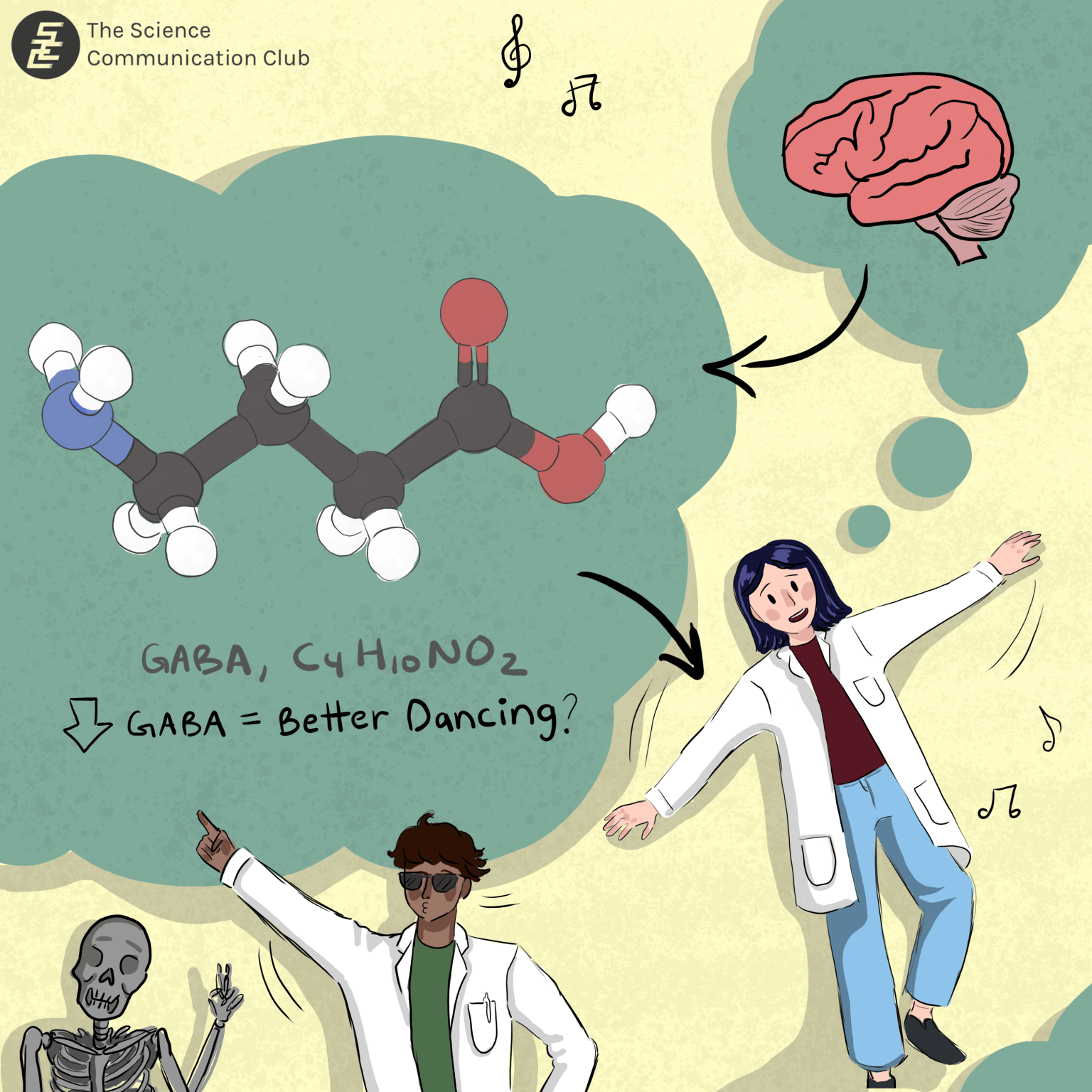

Several physiological factors beyond our control shape our dance moves, more specifically, our rhythmic abilities. For instance, researchers from McGill University and the University of Montreal have identified beat-deafness as an exceptionally rare deficit in biological rhythms, causing a mismatch between internal responses and external rhythmic cues.6 On the dancefloor, affected individuals have difficulty synchronizing their movement with the sounds they hear (i.e., they are unable to track the beat). This phenomenon sheds light on the complexity of neural function and its intricate relationship between rhythm perception and outward expression. Similarly, researchers at the University of Oxford have implicated a neurotransmitter in the brain, GABA, as an inhibitor of our ability to get our groove on.7 Their study reported a decrease in GABA levels induced by direct current stimulation to the brain, positively matched the degree of motor learning.7 In other words, it appears that our brain’s unique capacity to modulate GABA during learning correlates to our individual acquisition of new motor skills.7 Therefore, before blaming our unique dancing on our two left feet or insecurities, we should consider that new-found factors may be hindering us. Thankfully, as with any discipline, practice is our best bet in mastering the ballroom.

Dancing is considered an art, yet there’s a lot of science behind why and how our bodies evolved to perform slick moves, like the moonwalk, to eloquent sequences such as those in the Nutcracker ballet. Despite uncertainty and dispute, scientists all agree that to dance is truly human. It’s in our nature.

So, whenever we’re gifted the moment to shine on the dance floor, we should simply let our body do what it has evolved to do.

Let loose and dance!

Sources:

- Laland K, Wilkins C, Clayton N. The evolution of dance. Curr. Biol. 2016 [accessed 2023 Nov 5];26(1):R5-R9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982215014256. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.031.

- Dingfelder SF. Dance, dance evolution. Monit. Psychol. 2010 [accessed 2023 Oct 23];41(4):40. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/04/dance.

- Bibeau N. I trained as a dancer for 15 years, but I never knew why dance was so important to me – until now. 2022. CBC DOCS; [accessed 2023 Oct 23]. https://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/the-nature-of-things/i-trained-as-a-dancer-for-15-years-but-i-never-knew-why-dance-was-so-important-to-me-until-now-1.6362035.

- Kragness HE, Ullah F, Chan E, Moses R, Cirelli LK. Tiny Dancers: Effects of Musical Familiarity and Tempo on Children’s Free Dancing. Dev. Psychol. 2022 [accessed 2023 Nov 5];58(7):1277-1285. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fdev0001363. doi:10.1037/dev0001363.

- Chaplin LN, Norton MI. Why we think we can’t dance: theory of mind and children’s desire to perform. Child Dev. 2015 [accessed 2023 Oct 23];86(2):651-658. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.12314. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12314.

- So, you think you can clap to the beat?. 2014. McGill Channels; [accessed 2023 Oct 23]. https://www.mcgill.ca/channels/news/so-you-think-you-can-clap-beat-239990.

- Stagg CJ, Bachtiar V, Johansen-Berg H. The role of GABA in human motor learning. Curr. Biol. 2011 [accessed 2023 Oct 23];21:480-484. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21376596/. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.069.